"But those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty." -John 4:14

Tuesday, August 18, 2015

The Law and The Land: Part Four

"Honor your father and your mother, so that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you."

Exodus 20:12

When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.

John 19:26-27

Recap on the series: The Ten Commandments are not just for private morality. They're also an excellent tool to help people of faith start thinking and talking about justice and equality in our society.

The fourth commandment begins what many in the Christian tradition call the "second table" of the Ten Commandments: that is, the laws that govern human interactions with one another rather than our interactions with God.

To be honest, when I'm teaching middle school students, I spend the least amount of time by far on the Fourth Commandment, not because it isn't important, but because it's self-explanatory, and because dwelling on it too much seems to play into the (not entirely false) perception that pastors, teachers and parents have entered into a vast world-wide conspiracy against adolescents. I just don't feel like spending more than twenty minutes or so on "Hey, you whipper-snappers, you better mind your folks now, ya hear?"

But then...there's Jesus. See, Jesus had what most would call an unconventional view of family. Which is not to say he didn't love his family, or think family is important. It was just that Jesus saw the ethical laziness of which humankind was guilty: our impulse to put family first, getting twisted into an excuse not to care for the other. He saw how easily we rush to war against someone else's sons and daughters, to protect our own; how quick we are to cheat someone else's mother or father, if it's somehow on behalf of our own.

God made us with an incredibly strong bond with our family units. So strong that even if our families are really messed up, we will actually seek out messed up people to "love" us in the same dysfunctional way. What God placed in our hearts in order for us to protect and care for one another, can be twisted into just another excuse to hurt each other.

And yet, Jesus did not mean to throw the baby out with the bathwater. He didn't force his followers to cut all ties with their families. In fact, he criticized the Pharisees for doing just that: using their commitment to faith, as an excuse not to care for their earthly families. Our families should be training grounds for compassion. We should love our families, and we should take care of those whom God gives us, not because we're not responsible for anybody else, but to learn how to care for everybody else.

The social justice connection I see here is quite simple. From the cross, Jesus made a connection between two unrelated people: Mary, his mother, and the disciple whom he loves. They become family then and there, not through blood or birth, but by his word, and because they need each other. I believe Jesus says the same to us all. As we look at the millions of senior citizens living in poverty in our country, more than half of whom are women, Jesus says, "Here is your mother." When we consider the pay gap between women and men (still 78 cents on the dollar) that has barely budged in a decade, and that it's worse for women of color, Jesus says, "Here is your mother."

Your mother is poor. Your mother is a victim of discrimination. Your mother is an undocumented immigrant. Your mother is a senior citizen, living in quiet poverty. Your mother is homeless. Our family is not just those who look like us or live in our house. Our family is all the people whom we have the ability to care for, wherever we are, with little decisions we make. And yes, we can begin to honor them by honoring the family we grew up with. But in Christ, it never ends there.

Wednesday, August 5, 2015

The Law and the Land: Part Three

Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy. For six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and consecrated it.

Exodus 20:8-11

Then he said to them, ‘The Sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the Sabbath; so the Son of Man is lord even of the Sabbath.’

Mark 2:27-28

It's been quite a few weeks since I've been able to post, and it's been full of lots of really good "God-stuff" that I'd love to post about at a later time, but this one's been cooking for a while and it's time to get it out there.

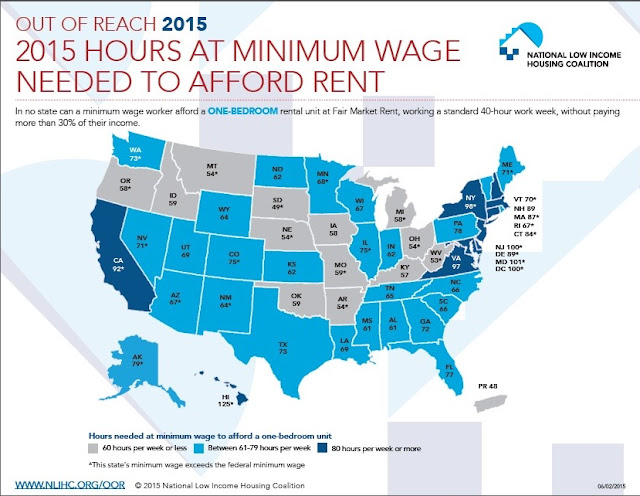

Let me explain what you see above.

THE MAP: This is from a report by the National Low Income Housing Commission. It lists the amount of hours in a week you'd have to work in order to afford a one-bedroom apartment. For easy reference, the gray states are "less than 60 hours/week", the light blue are "61-79 hours/week" and the dark blue are "80 or more". The states with an asterisk next to them are states that already have a minimum wage higher than the federal minimum wage. Maryland comes in at a modest second, with 101 hours per week. A single worker, no spouse or kids, making minimum wage, looking just to put a roof over his/her head, would have to work 101 hours every single week.

THE FIRST BIBLE VERSE. That would be the Third Commandment. It's the wordiest of the ten (depending on how you count), and it seems to be so wordy because God wants to make one thing absolutely clear: The Sabbath is not just for one class of people. It's for everybody. Your kids. Your employees. Your pack animals. Even complete strangers from foreign cultures who are hanging out in your general vicinity. And God is telling you this because it is your responsibility to make sure this is an option for those over whom you have influence.

THE SECOND BIBLE VERSE. Here we have the Son of God--Jesus Christ--declaring NOT that the Sabbath isn't important or that Christians shouldn't keep it anymore, but rather that it should not be used as a legalistic burden to heap on those already struggling to feed themselves. Jesus and his disciples are picking grain on the Sabbath because they haven't got any food, and the Pharisees invite them to a sumptuous Sabbath feast where they can fill their bellies to their hearts' content. Wait, no...turns out they get all bent out of shape and judge them for breaking the Sabbath, while offering precisely 0.0 solutions as to how they can both keep God's law and not go hungry. Huh.

So here's what I'm thinking today. It is admirable, of course, for Christian businesses to close their doors on Sunday. It is expected that Jews, Muslims and Christians--all who take God's commandment seriously--will take time in the week to rest, to reflect, to worship, and to simply let God be God. We all need time as a community to remember that by God's grace, the world keeps turning even when we're not running. These are all good things.

But I would submit to you that the third commandment was phrased in such careful legal language because it is so easy to break it by proxy. It's not just about you. It's about everyone whom your life touches.

And I'd further submit that if your business is closed on Sunday but your workers have to go someplace else and work a ten or twelve hour shift to make ends meet, you might still have a third-commandment issue on your hands. If you take time worshiping and resting with your family on Sunday, but you live in a state where a person couldn't possibly do the same on minimum wage, you might still have a third-commandment issue on your hands. In sum, this whole country has a great big hairy third-commandment issue on its hands, and it's high time we did some praying about how best to fix it.

Wednesday, June 3, 2015

The Law and the Land: Part Two

"You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God, for the Lord will not acquit anyone who misuses his name."

Exodus 20:7

"If the gospel we preach is not good news for the poor, it’s not the gospel."

Jim Wallis, commenting on Luke ch. 4

As a recap, in the wake of the Baltimore uprisings and the disturbing racial and economic inequalities across the country which it highlighted, I'm blogging about what those good ol' Ten Commandments--God's word to Israel from Mount Sinai, on how to be a free and faithful people--and what those commandments might have to say about social justice in our land today.

It's time for Commandment number two. And while I'm actually a bit more partial to the Reformed tradition in terms of numbering (they split up the Lutheran and Roman Catholic "First Commandment" into two: one about not having other gods and one about not making idols), I'm going to stick with my Lutheran roots, and move on to "our" second commandment, just because that's where I'm feeling a connection with the world this week.

If you grew up in a household like mine, you knew exactly what that second commandment was all about. You knew that God's last name is not "damnit", you even sometimes got called on an offhanded "Gosh!" or "Jeez!" and...admit it...even the now-ubiquitous "OMG" gets your hackles up a bit.

Putting it right out there, I'm not the best role model for this commandment, narrowly defined as not saying or using God's name unless you're legitimately talking about or to God. Not sure what went wrong--maybe exposed too early to the Indiana Jones movies--but I struggle.

See, the thing is, though, that "not saying curse words" is only the very tip of the iceberg. In the Small Catechism, Luther does with this commandment what he does best: takes a nice, simple, (relatively) easy-to-follow rule, and ruins it with all kinds of complications and implications and proactive suggestions. Sure, there's the "cursing and swearing part", that's pretty clear-cut. But then Luther goes on to include "lying" or "deceiving by God's name". A great young man I worked with in seminary, who came out of the Baptist tradition, called this "lyin' on God."

I think, if I made a full-court press, kept a "swear jar" in the kitchen, meditated every day, took a whole bunch of deep breaths before starting out on my morning commute, I might--mind you, might--be able to keep somewhat free and clear in terms of not saying the "J.C." word, or the "G.D." word, or generally cleaning up the potty-mouth. It's actually not a bad goal. But it's the "lyin' on God" thing that will always plague me, and the Body of Christ in general, because anything at all we have to say about God, we say from our perspective as human beings, bearing witness to Biblical texts written down by human beings, interpreted through the traditions of other human beings, and so in short, we will inevitably find out on occasion that what we'v had to say is utter and complete bulls--I mean, not as faithful a witness as we would like.

But when it comes to social justice, man oh man, the Church has done some lyin' on God through the centuries. We have used the Bible to justify wars, torture, slavery, racism, sexism, everything up to and including straight-up genocide, and by doing so we have taken God's name in vain in a way that no "swear-jar" could remedy. Even this week, I had a friend and colleague, who dared to suggest that Anti-Muslim Rhetoric is Un-Christian and Un-Biblical, get not just called names, but threatened, in Jesus' name. And just about every week, Christians will hear from pulpits across America that wealth and prosperity are a sign of God's blessing, and (sometimes implied but often said explicitly) that not having access to those things is a sign of God's anger. All this, in the name of the Son of God, who specifically said he was here to bring good news to the poor. The concept that God is mad at you or your community for being poor, or that ongoing poverty is somehow a just or inevitable situation, does not sound like "good news" to me. Sounds more like somebody is lyin' on God.

Obviously the burden for this one is heavy on pastors and church leaders, since it's our line of work to get up and talk about God in front of a big group of people every week. But here's the thing: What I as a pastor say about God from the pulpit gets heard by maybe 220 to 240 people on average. In my previous call, it was around 80 to 100. Now compare that to the hundreds of Facebook friends, or friends of friends, or followers on Twitter or Instagram, that may have the chance at reading every single thing you share, whether it's your original sentiment or someone else's. That could number in the thousands, easily. Every time. And I can guarantee you that 1) the majority of them do not come to church on a frequent basis, and 2) a good number of them will construe whatever you say from a "Christian" perspective, as what "all Christians" think or say. So it's up to us all: Let's not be lyin' on God.

So if you're wondering whether or not you're keeping the second commandment, here's a good rule of thumb. Talk about God in such a way where you could picture Jesus of Nazareth--Jesus who brought good news to the poor, Jesus who lambasted the religious leaders for empty piety without social justice--would be nodding along. Obviously, those are muddy waters, fraught with danger and uncertainty (welcome to the priesthood of all believers! This is hard!). If you're not sure how to navigate those waters, maybe just ask God. Near as I can tell, prayer is the only sure-fire, "second-commandment-safe" way to use God's name. But for the rest, there's grace.

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

The Law and the Land: Part One

"I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery; you shall have no other Gods before me." Exodus 20:1-2

"[Jesus] is God himself coming into the very depths of human existence for the sole purpose of striking off the chains of slavery, thereby freeing man from ungodly principalities and powers that hinder his relationship with God." -James Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 1968

So, I've been thinking. We all have. We've been thinking about Baltimore. About racism. About inequality, not just here, but across the country.

I've been thinking, and trying to be careful not to speak outside my realm of experience--I didn't grow up here, and even if I had, there's a good chance I would only have experienced one of what a colleague of mine called the "two Baltimores", historically divided both by race and by income--so I've tried to do a lot more listening than talking. I think that's a good policy for anybody, but especially for middle-class white guys like myself, it's a necessity right about now, if we're even going to start the process of changing a broken system.

As a Christian, part of my listening process is listening for God's voice: in scripture, in prayer, in the voices of my brothers and sisters in Christ. So as I've been listening, I've been wondering if God might have something relevant to say to us in the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17). It's an interfaith text: it's from the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, held sacred by both Jews and Christians. It's a text on which we Lutherans, as grace-focused as we are, have committed to do a lot of study. When we baptize kids, we promise to teach it to them. Luther wrote a short household book about them, meant to be taught by parents to their children, which in recent times many Christian families have "outsourced" to pastors, gathered around pizza with middle-school aged kids. It's the text that some Christians insist should be displayed in every courtroom across the land. So, as we listen to these words from God, I think they can and do have something to say about our "rules of engagement" in talking about inequality and systemic racism.

The First Commandment actually isn't a commandment at all. In fact, in Judaism, the first "word" of the ten is, "I am the Lord your God." This is a proper name: what we read in English as "the Lord" is the word YHWH, in Hebrew, "I am who I am", or, "I will be who I will be". It could be viewed as a deliberate dodge on God's part, when Moses asks God's name, as if to say, "You don't get to pin me down like that. I am who I am, and I'll be who I'll be." Except that, unlike when YHWH first calls to Moses from the burning bush, the Israelites already know at least one thing about YHWH--that YHWH has brought them out of the land of Egypt. That they are free people now, and that is YHWH's doing. Whoever else YHWH is, YHWH is the one who chose to liberate this nation of people from slavery. That is how God chooses to introduce God's self. The preamble to any other laws to be set forth. Setting people free is central to God's identity. I kind of wonder if that's on all these plaques some Christians want hanging above judges' heads.

And then we get to the Commandment itself: "You shall have no other gods before me." And if you ever were a squirmy middle-schooler in a Sunday School classroom, you probably know that this does not just mean you're off the hook if you don't have an incense burner and a statue of Baal or Zeus in your locker. It means, as Luther says, "We should fear, love and trust in God above all things." And then, if you're around my age, you probably did some sort of collage of magazine photos of various different stuff that can become your "god", like sports, friends, video games, money, etc...

But coming back to this as an adult, something rings true here: there are a lot of really important things about our who we are as a people that still have to take the back seat to God. Stuff that defines us as Americans. Stuff that many of our fellow Americans have lived and died for. Our rights. Our liberties. Our freedoms. Our constitution--which, though a very important document, and which I celebrate as a gift from God, was not divinely inspired. Capitalism and free enterprise. Hard work. Justice. Paying your way. This stuff is a big part of the American identity. But it's not divine. It's not God. It's not the one who freed the Israelites from slavery, and it's not the one who took on flesh and took our sin to the cross. And therefore, we can not put our ultimate trust in any of those things, and still call ourselves people of God.

Please understand, everything I just listed (and probably more that you can think of) can be a way that God's blessing is known and shared with people in our time and place in history. But they need to be held separate from God. They need to be looked at in God's light. We need to ask the question--especially when 20% of Americans own 85% of the wealth, while the working poor in Baltimore are getting targeted first for water shut-offs--"how might YHWH feel about this? Would the God who split open the sea to lead a nation from slavery to freedom, feel totally fine with the kind of wage-slavery that exists in some parts of our country?"

Short summary: God liberates. And American culture is not God.

And if you really think about it, that's actually some pretty darn good news, because to look around the world as it is, and think that what you see is God's best hope for humankind, would be a depressing thing indeed.

"[Jesus] is God himself coming into the very depths of human existence for the sole purpose of striking off the chains of slavery, thereby freeing man from ungodly principalities and powers that hinder his relationship with God." -James Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 1968

So, I've been thinking. We all have. We've been thinking about Baltimore. About racism. About inequality, not just here, but across the country.

I've been thinking, and trying to be careful not to speak outside my realm of experience--I didn't grow up here, and even if I had, there's a good chance I would only have experienced one of what a colleague of mine called the "two Baltimores", historically divided both by race and by income--so I've tried to do a lot more listening than talking. I think that's a good policy for anybody, but especially for middle-class white guys like myself, it's a necessity right about now, if we're even going to start the process of changing a broken system.

As a Christian, part of my listening process is listening for God's voice: in scripture, in prayer, in the voices of my brothers and sisters in Christ. So as I've been listening, I've been wondering if God might have something relevant to say to us in the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17). It's an interfaith text: it's from the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, held sacred by both Jews and Christians. It's a text on which we Lutherans, as grace-focused as we are, have committed to do a lot of study. When we baptize kids, we promise to teach it to them. Luther wrote a short household book about them, meant to be taught by parents to their children, which in recent times many Christian families have "outsourced" to pastors, gathered around pizza with middle-school aged kids. It's the text that some Christians insist should be displayed in every courtroom across the land. So, as we listen to these words from God, I think they can and do have something to say about our "rules of engagement" in talking about inequality and systemic racism.

The First Commandment actually isn't a commandment at all. In fact, in Judaism, the first "word" of the ten is, "I am the Lord your God." This is a proper name: what we read in English as "the Lord" is the word YHWH, in Hebrew, "I am who I am", or, "I will be who I will be". It could be viewed as a deliberate dodge on God's part, when Moses asks God's name, as if to say, "You don't get to pin me down like that. I am who I am, and I'll be who I'll be." Except that, unlike when YHWH first calls to Moses from the burning bush, the Israelites already know at least one thing about YHWH--that YHWH has brought them out of the land of Egypt. That they are free people now, and that is YHWH's doing. Whoever else YHWH is, YHWH is the one who chose to liberate this nation of people from slavery. That is how God chooses to introduce God's self. The preamble to any other laws to be set forth. Setting people free is central to God's identity. I kind of wonder if that's on all these plaques some Christians want hanging above judges' heads.

And then we get to the Commandment itself: "You shall have no other gods before me." And if you ever were a squirmy middle-schooler in a Sunday School classroom, you probably know that this does not just mean you're off the hook if you don't have an incense burner and a statue of Baal or Zeus in your locker. It means, as Luther says, "We should fear, love and trust in God above all things." And then, if you're around my age, you probably did some sort of collage of magazine photos of various different stuff that can become your "god", like sports, friends, video games, money, etc...

But coming back to this as an adult, something rings true here: there are a lot of really important things about our who we are as a people that still have to take the back seat to God. Stuff that defines us as Americans. Stuff that many of our fellow Americans have lived and died for. Our rights. Our liberties. Our freedoms. Our constitution--which, though a very important document, and which I celebrate as a gift from God, was not divinely inspired. Capitalism and free enterprise. Hard work. Justice. Paying your way. This stuff is a big part of the American identity. But it's not divine. It's not God. It's not the one who freed the Israelites from slavery, and it's not the one who took on flesh and took our sin to the cross. And therefore, we can not put our ultimate trust in any of those things, and still call ourselves people of God.

Please understand, everything I just listed (and probably more that you can think of) can be a way that God's blessing is known and shared with people in our time and place in history. But they need to be held separate from God. They need to be looked at in God's light. We need to ask the question--especially when 20% of Americans own 85% of the wealth, while the working poor in Baltimore are getting targeted first for water shut-offs--"how might YHWH feel about this? Would the God who split open the sea to lead a nation from slavery to freedom, feel totally fine with the kind of wage-slavery that exists in some parts of our country?"

Short summary: God liberates. And American culture is not God.

And if you really think about it, that's actually some pretty darn good news, because to look around the world as it is, and think that what you see is God's best hope for humankind, would be a depressing thing indeed.

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

Death of a Seed

"Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit."

John 12:24

Well, Holy Week is fast approaching. And of course, now is the time when my blogger-conscience starts bugging me about not having posted here in a good long while. But a solution presents itself: Below is the transcript of a sermon I preached this past Sunday (Lent 5B, March 22nd) that some have found useful. Hopefully you will, too. Blessings on your Holy Week and Easter.

Gospel text: John 12:20-33

It wouldn’t have occurred to

me

To think like a seed.

It’s an interesting window

into Jesus’ mind:

The way he sees people.

The way he sees us.

It wouldn’t have occurred

to me that to a seed,

Growth might not be an

attractive thing.

Even though growing is

what seeds have evolved over hundreds of millions of years to do, for an

individual seed,

who’s never been through

it,

It would be a death.

Your skin—your boundaries

of who you are—would be ruptured.

The only identity you’ve

ever known—a particular seed in a particular place and time—would cease to

exist.

A new thing would exist in

its place,

and what that is, you

can’t control.

It’s up to God.

Thinking like a seed, it’s

terrifying.

But thinking like a

farmer,

You realize it’s all the

seed is meant to do.

The only way to truly be

alive.

Jesus says, “Those who

love their life will lose it, and those who hate their life in this world will keep it for eternal

life.”

I don’t think Jesus means

that the only people who’ll go to Heaven are those who are in constant agony in

their earthly lives.

Based on how he uses the

word elsewhere, I think “hate” here means more like reject.

That if you cling to the identity the outside world

wants to give you, that outer shell, what you

consider to be your life will be very short.

But if you reject that identity, and admit it’s not who you are, then God can reveal to

you something deeper, something real,

something infinite.

If you’ve never been

through that kind of

growth, it is like dying. It’s letting go of who

you think you are, without being entirely

sure who by God’s action, you’ll become.

I mean, you know you can’t be a seed forever.

Transformation is coming.

It’s just a question of

whether you’ll enjoy becoming something more.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus

has a lot to say about “the world.” He

doesn’t just mean the physical, “earthly” realm as opposed to some separate “heavenly”

realm beyond the blue. It’s more of a shorthand for Jesus’ mission field—where

he works. That part of existence which doesn’t know him. That which needs to be

saved. That which rejects Jesus and his followers, yet which God still loves. It’s not a place so

much as a value system, an institution, a way of thinking, but also a spiritual

force.

It’s the dominant force in

the human spirit far too often, the part of us that values only the outer shell

of that seed:

what we can see, what we

can get, whom we can influence.

It’s the system in which

your identity is nothing more than a set of attributes: a pile of money and

possessions, the pages of a resume, the letters after your name, the number of

your Facebook friends or twitter followers, the number of employees who report

to you, the acreage of your territory, the way your body compares to a

photo-shopped body in a magazine.

It’s a system that tries

to make eternal, the things that are temporary, as though this life we see is

all there is.

It’s a system that ranks

us by the numbers, yet somehow makes sure none of us measures up.

And despite this constant

abuse, it’s a system in which we can get way too comfortable.

It’s like the pothole on

your commute that’s there for so long that you swerve without looking, or the aching

tooth that makes you chew all your food on the other side of your mouth.

It’s a status-quo that we

forget is even there.

Especially

if we’re benefitting from it.

If our power and prestige

is coming at the expense of injustice against someone else.

If our comfort comes at

the cost of others’ pain.

If that’s the reality of

this world, you can understand why so many choose not to see it.

Jesus says his kingdom is

not of this world.

But he’s not here to lead

us out of it either.

He’s here to drive the

ruler of this world out.

To take down the whole

system.

He’s here to show us

there’s another way:

A system of acceptance, instead

of rank.

A system of love, instead

of judgment.

A system of forgiveness,

instead of score-settling.

And the way he’s going to

do that is to be lifted up, for everyone to see, not on a throne, but on a

cross. Not by conquering, but by dying.

When Jesus says his hour

is coming, and that he’s going to glorify

God, that’s what he’s talking about. He’s talking about this moment, in

which he utterly rejects

everything the so-called “world”

has to offer.

When he rejects the lie,

that all that matters is how strong and pretty a single grain of wheat looks

like on the outside, and shows us that what really matters is the life that’s

growing on the inside.

When Jesus willingly

accepts the most shameful, painful place in this world’s system, he shows us that

even death itself is only a transformation,

and dying in the world’s eyes, is the pathway to being truly alive in God.

When we die to

ourselves—to our selfishness, our need to be the best and the strongest—we can

live for others, and for God. We can start living the resurrection life Jesus

promises,

Even now.

In Baptism, we died in the

world’s eyes.

We renounced the powers of

this world that rebel against God. We rejected the identity, the status, the rank that the world wanted to give us.

That identity got left down there in the water, like the outer shell of a seed.

God connected us to the

death of Jesus,

And the Holy Spirit then

gave birth to our new

Identity: an identity that

has nothing to do with what we have, or look like, or can accomplish, and

everything to do with God’s love for

us.

That’s where the growth

starts.

That’s where the

transformation starts.

There in the water.

It really should give us

pause.

It should be a little daunting,

giving up the false

personae that the world gives us, and not knowing what God’s growing us into.

It might be more

comfortable to feel as though nothing will change—that the rules of this world

will always apply. Once a seed, always a seed.

But God wants so much more

than comfort for us. God wants transformation. Growth. Death…and resurrection.

And through Jesus, we

receive it.

Amen.

Monday, February 2, 2015

Hitting the Road of Faith

"Immediately the father of the child cried out, ‘I believe; help my unbelief!’"

Mark 9:24

"Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, ‘Peace be with you.’ Then he said to Thomas, ‘Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.’" John 20:26b-27

About ten days ago, I spent a truly inspired weekend in Ocean City with around 360 youth plus adult advisors and staff: The Delaware/Maryland Synod's "RoadTrip" retreat for High School students.

There were many highlights: playing music with talented, hard-working young people from all over Maryland, watching the energy and enthusiasm of young people in the large group times, hearing the impact of small group discussions on Salem's young people, even hearing the entire Gospel of Mark, in a way I'd never heard it before: embodied, by a story-teller who knew it by heart.

But among those highlights for me was sitting as an audience member for the "Open Mic" event last Saturday night. Young people got up, shared music (including some rather spectacular beat-boxing), and a few spoken-word reflections: one of which is sticking with me. One young person shared a poem that was breathtakingly honest about her doubts: doubts about God, about the afterlife, and about much of what we proclaim as Christians. It was a tremendously brave thing to do, although less so because of the other young people (who are, after all, trying to figure this thing out themselves) than because of us uptight adult-leader folks (who are supposed to have it figured out by now, and be figuring it out for those young people too!). I can imagine how the "grown-ups" in the faith may have squirmed in our seats a bit listening to what not only this young woman, but all of us, have questioned from time to time in our lives.

What struck me more than anything about this reflection was how humble it was. It was so far from any kind of "final declaration" or "creed", so far from having it all figured out, much less figure it out for others, so clear about this moment in time, as one step in the journey.

It was many years ago now that I came to terms with doubt as a part of faith. It's not something to fear or to squash. It's par for the course. In fact, it can be helpful, because it does keep us humble. It curbs our hubris. It shuts our mouths when we might rush in where angels fear to tread. It warns us of Adam and Eve's desire to "know good from evil", and thereby "be like God." We don't. We can't. Not fully.

Doubt is a constant companion on our journey. But it is not the destination, any more than belief is. That's where I think we can get tripped up. Living through the 20th century and into the 21st, I feel like we have seen the dangers of getting trapped in the certainty of "belief": hemming ourselves in with a set of doctrines, never to be questioned, immune to growth and change, set in our ways, ready to settle into our comfortable Hobbit-holes with our doctrines as companions. The certainty of "belief" (as distinct from "faith") is dangerous, and we know it. That kind of unquestioning certainty has lead to unspeakable violence, and still does.

But we need to also talk about the "certainty of doubt." By this, I mean the doubts we get comfortable with. The doubts that frame our worldview. The mental asterisks we put next to various words and phrases every time we get up and say the creed, the asterisks that ave grown almost as important to us as anything that's written there. Often, these doubts are much more hard-won, the result of much more struggle and sleepless nights, than the beliefs we have never had trouble with. It's understandable that we would hold those doubts close to us: even that they, too, would become our living companions in our settled Hobbit-holes.

But here's the thing: whether you worship every week or not at all, whether you're a fundamentalist or a settled agnostic, God is going to knock on the door at some point, and invite you back out on the road. You are not a finished product. Your doubts, your beliefs, your struggles and triumphs, your strengths and weaknesses, are all part of your faith. And faith is not a Hobbit-hole. It is the road itself.

The week before last, with a lot of others I took a moment to remember the life and work of Marcus Borg , an acclaimed New Testament scholar, a voice in the progressive Christian movement, and (probably most notoriously) a member of the Jesus Seminar. In the latter role, he helped to develop a consensus among scholars as to how historically verifiable the Biblical sayings and deeds of Jesus were. I think the gift this was to the Church is often misunderstood: rather than telling anyone what (not) to believe, it established the things about Jesus on which any serious-minded person of any (or no) faith could agree. It essentially set the boundary-line for where our knowledge ends and our beliefs begin.

But Borg's contributions were much more important than that one collaboration. In his book, The Meaning of Jesus, Borg writes:

"Among some Christians, [the phrase "Jesus died for your sins"] is seen as an essential doctrinal element in the Christian belief system. Seen this way, it becomes a doctrinal requirement: we are made right with God by believing that Jesus is the sacrifice. The system of requirements remains, and believing in Jesus is the new requirement. Seeing it as a metaphorical proclamation of the radical grace of God leads to a very different understanding. “Jesus died for our sins” means the abolition of the system of requirements, not the establishment of a new system of requirements.”

The core of his work, as I understand it, seems to be drilling down to the essential message of Jesus, and the way of Jesus, rather than a system of beliefs about Jesus. I'm thankful for his perspective.

We all have beliefs about Jesus. And some doubts about him, too. The road of faith includes both: moving on from where we are, with Jesus and our fellow disciples as companions, willing to be changed by that journey. Some beliefs may become doubts. Some doubts may become beliefs. Trusting in Jesus is trusting that when we "hit the road" with him, we have nothing to fear, even if the road changes us. The grace has claimed us already. It's time to go exploring.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)